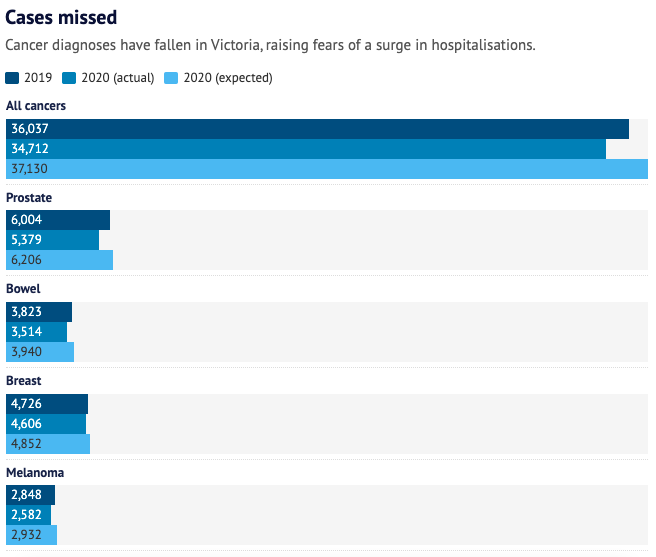

Prostate and bowel cancers and melanoma were among the most overlooked cancers in Victoria last year as COVID-19 lockdowns left thousands of people with ignored or missed disease.

The state’s overstretched healthcare system is bracing for a surge in advanced cancer cases and demand for urgent treatment. The authors of a long-awaited Victorian Cancer Registry report, released on Thursday, have warned the state’s medical system is in uncharted territory.

The impacts of the backlog of missed screenings and diagnoses are likely to cascade throughout the healthcare system over months and possibly years to come. Senior oncologists say they are seeing cancer patients with more advanced stages of cancer and people are still putting off specialist appointments.

Fears of catching COVID-19, difficulty accessing medical services and a fall in face-to-face medical care have caused many to avoid medical appointments, routine checks or follow-up examinations.

The Cancer Council of Victoria’s chief executive, Todd Harper, said the decline in cancer diagnoses had left Victoria’s healthcare system in “completely uncharted territory”.

“We need to promote the importance of not delaying and encouraging people to reach out to organisations offering supportive care for cancer,” he said.

Prostate cancer was one of the most undiagnosed in Victoria last year, the registry shows, with diagnoses falling 13 per cent.

Prostate cancer accounts for nearly a third of all cancers for men, whom the registry has identified as being at greater risk of having their cancer diagnoses missed during COVID-19.

Between March and April last year, the number of colonoscopies used to diagnose bowel cancers fell by more than half across Australia, a recent Cancer Australia study showed. In Victoria, the state’s registry reveals an 11 per cent drop in bowel cancer diagnoses.

Cancer registry director Sue Evans said COVID-19 lockdowns had resulted in a “break in the chain” for cancer diagnosis. This would place huge demand on operating theatres and radiotherapy centres in hospitals that were already straining under the pressures of COVID-19, she said.

“All of those [services] will need to be able to be given capacity to operate, and perhaps at times where services have traditionally closed down, over Christmas periods, that won’t happen for a while yet until we’ve caught up,” she said.

Overall, there were 2420 fewer cancer diagnoses in 2020 compared with 2019, a 7 per cent drop. Those who were not diagnosed were largely men, people aged 50 to 74 and residents of major cities.

Melanoma diagnoses fell 11 per cent, mostly among those in the early stages of the disease.

The Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre has seen a fall of about 25 to 30 per cent in presentations for skin and prostate cancers, according to the hospital’s radiation oncologist, David Kok.

Patients were increasingly going to hospital when they were symptomatic and at a more advanced stage of cancer, requiring more intensive treatments, Dr Kok said.

Even after diagnosis, some patients were delaying attending a specialist or follow-up appointments, owing to fears of entering hospitals, he said.

While telehealth had brought “huge advantages” during the pandemic, the absence of physical interactions with GPs meant early signs of cancer were being missed, which was especially the case for skin checks or prostate cancer tests, Dr Kok said.

“It’s very common for patients to come in and a doctor may incidentally notice something that requires the check, or maybe patients feel enabled to say, ‘While we’re there, can you have a look at this?’ So, the additional minor checks are things which are probably less likely to happen on a telehealth interview.”

The start of last year’s first lockdown prompted the temporary suspension of breast screening services, forcing many to wait several months before getting a check. Only at-risk patients were prioritised for most of last year.

The registry shows breast cancer diagnoses dropped early last year but improved slightly in following months, with a 5 per cent decline reported by the end of the year.

When Anne Elliott called her local clinic to schedule a mammogram in November last year, she was told the service had a huge backlog, and she would be put on a waiting list as she had no symptoms or family history of breast cancer.

But she had a “bee in her bonnet” and persisted, partly due to “instinct” and a news article she had read about a breast cancer patient.

The clinic squeezed her in a fortnight later, and within a month Ms Elliott was diagnosed with high-grade ductal carcinoma. The cancer was caught early, but it had still grown to 13 centimetres, and she needed a mastectomy.

The single mother of two young boys has had four surgeries this year, including an immediate breast reconstruction. Occasionally, because of COVID-19 restrictions, her boys couldn’t visit her in hospital.

The process was painful, but Ms Elliott is thankful she caught her cancer early and says her story sends a clear message.

“When people were in lockdown and struggling to work from home, juggling homeschooling, there wasn’t time to go and book in these things. And there might have been barriers once you try to book in,” she said.

“No matter how busy [you] are, particularly as single mums and parents that work, don’t put off your health.”

Victoria’s Health Department has been briefed on the gaps in cancer diagnoses, with a taskforce comprising clinicians and policymakers that was established early in 2020 meeting regularly to prepare for the impending crisis.

A spokesman said the department was working closely with health services to increase cancer screening participation, and “a number of strategies” are being implemented to support catch-up of missed screens during COVID-19.

“We encourage all Victorians to participate in cancer screening and continue to seek medical care if they are experiencing symptoms,” he said.

“In the Victorian budget 2021/22, the government invested $91 million to help Victorians catch up on deferred care, including cancer screening for those who may have missed or delayed services during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

This article was written by Timna Jacks in The Age. Click here to read the article.